Mindful of the impending inquest verdict for the Roy Butler case, I’m sharing an interview with a professor who acted as an expert witness at an inquest involving antibiotic medication, earlier this year.

Professor of Psychiatry Dr David Healy was a witness at the inquest into the death of a 17 year old boy, who died two weeks after he began taking the antibiotic, doxycycline, for the treatment of acne.

This interview was conducted a few days before Roy Butler’s inquest got underway in Cork.

Dr David Healy runs a website, which acts as a ‘Database of Medicine’, where tens of thousands of reports of adverse effects from pharmaceutical medicines and vaccines have been logged since its launch in 2012.

Dr Healy came onto my radar via another family who had been through the inquest process following the death of their son Darren Connell (17), who took his own life two weeks after commencement of doxycycline.

Dr Healy acted as an expert witness for the Connell family at this inquest and the coroner described his evidence as ‘compelling.’ An open verdict was recorded. The Connell family continue their efforts on behalf of their son and I hope to document their most recent achievements on this Substack in the coming weeks.

Beginning this interview with Dr Healy, I raised the (then) upcoming inquest into the death of Roy Butler (23), who suffered a massive brain haemorrhage and died five days after his covid Janssen (Johnson and Johnson) vaccine. We discussed the case in terms of clinical trial data, the process of an inquest, evidence from medical professionals at inquests and the nature of different verdicts.

Dr Healy’s concluding remarks are pertinent in relation to the Roy Butler case and echo what was heard at the inquest: that Roy was fit and healthy, became immediately unwell after his Janssen shot and then documented his decline in a series of texts over the next four days, saying repeatedly, that he was unwell because of the vaccine.

Remember that Dr Healy spoke these words before Roy Butler’s inquest began:

“It’s a common sense call that a drug has caused the harm, or a vaccine has caused it.

You may not be absolutely sure but absolute certainty is not actually compatible with human life, you need to make a judgement call that it’s highly probable.

“In legal cases the medical standard is to a reasonable degree of medical certainty -

This means, is there anything else that’s more likely than the vaccine to have caused it and if there isn’t anything else more likely than the vaccine to have caused it then the operating hypothesis has to be, the vaccine caused it and if it’s a case of giving the person the next dose, don’t do it.”

The topic of Expert and Independent witnesses features as part of the Coroners Society of Ireland Annual General Meeting in Co Mayo this weekend, with a presentation from Senior Counsel Luan Ó Braonáin SC.

Interview:

LR: I'm on the line with Professor David Healy.

David, would you mind just outlining your own background briefly for us, please?

DH: Yes, I'm a professor of psychiatry, but I've worked in three different universities over the years, and the main thing I do is I have a company called Database Medicine, which has a website called RxISK.org where people can report the adverse effects that they have on the treatments that they may be on.

LR: And how long is that website in operation?

DH: It has been in operation since about 2012, so about 12 years now.

LR: And would you have any idea how much activity it has attracted?

How many people have recorded adverse reactions from different medications?

DH: That's a great question.

Unfortunately, I'm not the kind of person that keeps track of the figures like that.

I get quite a few reports each day about different drugs that people are on and different kind of problems that they have. So I guess it's possibly tens of thousands of reports.

Now, until quite recently I'd have said we were at a website that had most reports from people on treatment reporting natural problems. Places like FDA and the regulator in the UK and Europe, they've all had kind of websites which until recently were websites where the company reported problems are doctors reporting problems.

You know, it was easy for me to say that we were actually having more reports from the people who were on the treatment. That's probably changed, you know, there's an increasing number of people that are reporting to FDA that they've actually had problems on treatment.

Coming to the vaccines, I think most reports have actually come from the people, either to MHRA in the UK, EMA, or the CDC over in the United States.

Sorry about being hoarse, this is very strange for me.

LR: OK, well, you take a drink when you need to and otherwise we'll just keep going as best we can. So I'll start with my first question then.

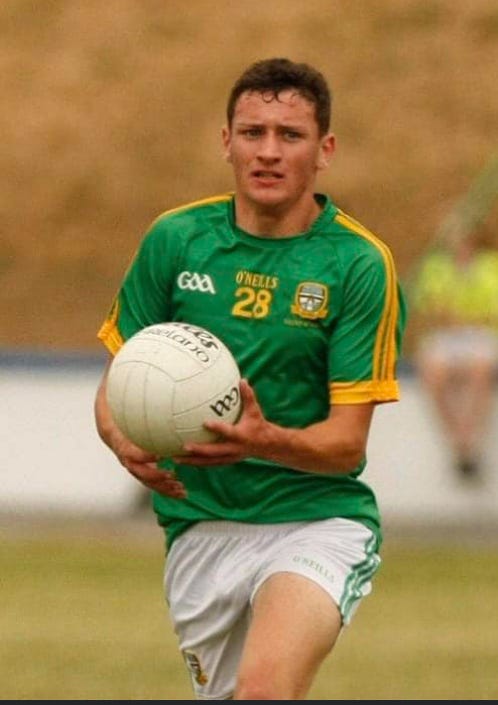

I'm speaking to you ahead of an inquest that's taking place in Cork in Ireland next week and it's in relation to a young a fit healthy young man, a footballer, Roy Butler. And he took the one shot COVID Janssen vaccine and he died five days later are you familiar with the with the Janssen COVID vaccine as in are you familiar with the safety trials clinical trial process that that went through yes okay could you talk a little bit about it?

DH: Yes well, in terms of all of the vaccines, they've all been through clinical trials, that on the face of it, look like they've been very big clinical trials. Big clinical trials in the sense that they've recruited thousands of patients, and they've done so in extremely short periods of time. Now, when we talk about clinical trials, you need to know that these things are run by companies that run clinical trials.

They're not run by universities or hospitals or even the pharmaceutical industry these days. And the company that runs the trials, well, what's the best way to explain this? The companies that run these trials ultimately end up holding the data from the trials. I mean, what they do is they recruit patients from a number of different centres and from a range of different countries and the data all goes back to the company helping run the trial and they're the ones who actually hold on to the data per se and usually hold on to it offshore so if you're in Ireland, the HPRA or Europe – the EMA and you ask to see the data you usually can't get to see it what you get to see is a report that's written up by the company that ran the trial. And they may make access to certain figures from the trial available to the regulators.

And when I say that, I mean, for instance, you have an SPSS spreadsheet which says, look, you know, the response to the vaccine in terms of the antibodies in the case of the 10,000 or maybe 20,000 people that we had in this trial looks like this, and the response on the placebo looks like that.

So the regulators may get a spreadsheet with a lot of figures in it, but that's not the data.

The data is people like you and me, if we were actually involved in the trial, and if our involvement gives rise to figures.

If you want to find out what happened in the trial, you have to have your name and my name, and you have to be able to get in touch with us and say, look, this says you may have had a blood clot during the course of this trial. Can you tell us more about what happened? And you may find out that, well, you didn't just have a minor blood clot, they had an awfully serious blood clot, which meant that they ended up in ICU, and they're now suffering the effects of some kind of stroke. They're not fully operational in the way they once were.

So in order to understand what actually happened in this trial, you need to have the contact details of the participants.

And the regulators don't ever get that. They don't check into the data.

No one other than the company that runs the actual trial who has data like that.

People assume that the authors on the articles in the New England Journal of Medicine or whatever, who write up themselves and who appear to be working in the clinical trial centres that recruited the patients to the trial, they'll have actually seen the patients and they'll know that, yes, the article that you see in the New England Journal of Medicine is a fair representation of what actually happened in this trial.

But in fact, the authors in the authorship line of these articles haven't written the article and haven't seen the data. And often won't have seen the patients coming through their own clinical trial centre either.

Sometimes we know that there have been problems, but these investigators agree to hide the problem or to make the problem disappear. And there are loads of different ways that the company running the trial can help investigators make the problem disappear.

LR: OK, so you have the clinical trial and then you have an emergency authorisation process.

Do you think the way this is being done, and particularly this emergency authorisation process, does that put the public at risk? Specifically by what you're saying, that there isn't any long term follow up with the people who partake in these trials?

DH: Well, if you have a major crisis where we've got a lethal virus here, you risk being killed, and we, the FDA, or EMA are in the business of trying to make sure that you can get access to a vaccine that may prevent you from having the problem.

That's what the emergency authorization process does. It gets your vaccine on the market quicker than it would otherwise get there. It's not full approval. And one of the issues was it was very unclear with the full approval why there was a big rush to get full approval. The emergency use authorization, you know, they had some data, they were able to look at some data. What the regulators were looking at looked relatively okay. Although we now know that what they were looking at was false and misleading.

So that they could say, well, yes, you know, it's worthwhile in the circumstances, even though we know the full risk, given the gravity of the problem, it's worthwhile to authorize this vaccine on an emergency basis.

But regulators didn't have to go ahead to full approval. They did go ahead and approve it long before they had the long-term follow-up data. You know, this, and the vaccines were approved six months after the emergency used to be approval.

And the difference with the full approval, which they didn't in a sense have to do, is they could then mandate a vaccine.

You can't actually force people to have a vaccine that's only on the market in terms of emergency use. But full approval lets you force people. If you're working in healthcare and even if you're pregnant, you can be told you have no option but to get the vaccine and if you don't get the vaccine, you're going to lose your job.

And there's tons of people around the place working in healthcare and elsewhere that actually lost their jobs because they were mandated to get the vaccine.

We didn't have a lot more information six months later as to the safety of the vaccine or the efficacy of the vaccine.

You could even say the regulators should have been in a better position to realize that actually these vaccines didn't work as well as we were being told and they weren't as safe as we were being told, but they went ahead and approved them.

And as I say, a lot of people, pregnant women in particular, were faced with the option of getting this vaccine and we didn't know the safety of it or else they were going to lose their job.

And lots of people opted not to take the vaccine.

So, you know, we ended up with a pretty grim kind of situation.

LR: Well, in relation to this inquest, Roy Butler took the vaccine in order to access the gym and in order to travel. What are your thoughts on a government introducing lockdown restrictions like that and then offering a course to freedom, shall we say, through taking a vaccine that we don't have any long term or even enough short-term information about what it might do to a person?

DH: I think that's grim.

There's been a load of people that I've seen … seriously injured by the different vaccines that they've had. They say they took because they want to travel you know it's kind of really normal to want to travel and if you've been told that the vaccine works very well and is safe a lot of people will say well look there's no real risk here.

And if I don't take the vaccine, I'm not going to be able to do things that I like to do.

So I think a lot of people ended up in this boat. So you had, even before the mandates were introduced, you had an informal mandate. And I think that was pretty grim. Against this background, we weren't being told, look, there is a risk to doing all this. We think it's a good idea that we have a lockdown. We think it's a good idea that people who aren't vaccinated can travel. But we also know that there's a risk to have the vaccine. People weren't being told that extra bit. They were told there's no risk to having the vaccine. It was the kind of thing that seduced people into making a trade-off that if they'd been told the truth they might have been a little less likely to make.

LR: Exactly. Because it touches on the whole topic of informed consent to a medical intervention. But we were repeatedly told, like a mantra, these products are safe and effective, safe and effective.

But in actual fact, I would wonder how many people did offer their full informed consent for these products.

DH: Well, I probably need to email you an article where I look into this. And in the case of the AstraZeneca trial, for instance, and the Pfizer trial, I don't remember if we had a Janssen patient in the mix. No, I think it was a Moderna patient.

But anyway, yeah. I had two or three different patients who were significantly injured in the clinical trials. Now, to get into a clinical trial of any of the vaccines, you had to actually sign an informed consent form. And the informed consent form of the Pfizer vaccine and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and the other vaccines all said, look, if you have any injury in the course of this clinical trial, other than an injury, say, for instance, in the vaccine, let's say you slipped on a banana skin, which is not the kind of thing a vaccine has caused, then anything that has actually happened to you that could be caused by a vaccine, the company will clearly pay the cost of all the treatments that you needed, all the investigations.

But in fact, what happened to the people that I've been in touch with is that the company refused to concede that the vaccine has anything to do with the very obvious harms these people have had.

I wrote an article on all this about the fact that, in this case, the info content in the clinical trial was not valid. And I think that's true for all of us.

The general sense we had was that if we were injured by the vaccine, taking risks in order to reduce the risk to others...and that, you know, the health services or whatever would actually cover the costs and ensure that we got good care and ensure that we didn't have this money.

But that's not what happened.

You know, there was a denial that any of the injuries we had that were obviously caused by the vaccine could have been caused by the vaccine. So in a sense, it was all put down to problems in us

And this meant that a whole load of people had to pay for their own health care.

And where people’s health care was covered by insurance, they would find their insurance premiums going up because, you know, the insurance companies couldn't get the money back from people making the vaccine or from anyone else.

And vaccine compensation programs...had been in place until recently have been pretty well dismantled.

There have been small amounts of compensation in the UK, but I don't know about the situation in Ireland or the situation in the United States. I don't know.

There's been no compensation.

LR: Say that last word again?

There's been no compensation.

LR: Compensation. Okay.

LR: So the reason I'm talking to you today, Professor Healy, is because of your involvement in an inquest in County Meath last year, the inquest into the death of a teenager, Darren Connell. And Darren took his own life shortly after commencing medication prescribed by his GP for acne, the treatment of acne.

What are your thoughts on the inquest process in general? Because I presume in the UK, the inquest process is largely similar. The one operating here in Ireland is based on the one in the UK historically.

So how do you find the whole process in relation to uncovering issues with pharmaceutical products in general, like trying to navigate the inquest process for a family's sake?

DH:

Yeah, the inquest process isn't actually designed to look at the role that a drug may have played in the death of the person whose inquest it is. A coroner in Ireland and the U.K., doesn't have an option to blame a prescription drug or vaccine as causing the deaths.

They fall back on the idea, well, we're just in the business of trying to decide, did the person die from a blood clot?

We're not in the business of trying to say the vaccine or the drug caused the blood clot or the suicide or whatever. In the case of a street drug, that's known to cause blood clots, to cause people to commit suicide - to blame the drug. They have a box they can tick saying the street drug caused this problem. But they don't have a box they can tick that says the prescription drug caused this problem.

LR Okay, interesting.

DH: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. And part of what begins to happen at an inquest is that the coroner will usually call the patient's doctor in as well, and then they ask them, do you think the vaccine or the drug caused the problem that this person has had?

The doctor, before they go into an inquest, will have their own insurer and will have been in touch with them and will say, look, I've been called into this inquest when my patient had a vaccine and they died or they've been on this drug and they've gone on to suicide and how do you think I should handle it?

And the lawyer for the insurer will say, well, you don't blame the drug or the vaccine. And even if it's an obvious case, a drug obviously causes a problem, or the vaccine obviously causes a problem, the insurer will say to the doctor, if you can't say that, if you can't say, well, look, you know, blood clots happen, they can kill people, or, you know, acne is an awfully serious illness that causes teenagers to get depressed and to think they're trying to kill themselves, if you find that you can't say that, let our lawyer do the talking for you. And, you know, what happens then is at the inquest, the coroner hears the lawyer or the doctor saying, no, the drug didn't cause a problem, this is awful illness this person had and these things happen, etc., etc. And the regulator, EMA or whoever, if they get a report from the inquest. They say, well, look, okay, we have a report, and it looks like to the coroner, a lay person, a legal person, you know, they think its obvious the drug or the vaccine caused this. But they are not medically trained, and we'd like to know what the doctor said. And the inquest transcript will show the doctor didn't say, or else they said nothing, or else they said, no, no, no, no, I think this person just unfortunately had a coincidental death, or they had this obviously serious illness, they had an acne spot, and that clearly led them to think about killing themselves. So, inquests are tricky situations. Doctor gets advised to take the position outlined for them by their insurer. If a doctor thinks a vaccine or a drug caused a problem, there is a risk that you could be charged with involuntary homicide. The insurer will put it as bluntly as that, which scares a lot of doctors from saying anything.

LR: What do you mean it scares a lot of doctors off? As in it scares them to tell the truth at an inquest? Is that what you mean?

DH: It scares them to tell the truth at the inquest. They figure there's a real risk if the patient's family thought anything I did caused the problem that they may take a legal action against me. Now, the insurance company is really trying to save on legal costs for them, but a doctor has a duty to the person who's dead and to their family.